With many famous names in hospitality presenting uniformity in appearance and approach, Alan Swaby looks at one group of hotels that prides itself on offering superior service and hospitality from breathtaking locations.

Don’t you just love rags-to-riches stories? Well in this case, the story doesn’t exactly begin with ‘rags’—but it’s certainly a tale of a man who punched above his weight, was never afraid to take chances and continually seized every opportunity that came his way.

And the story does end in riches—not surprisingly, as we are talking about a hotel group that is continually rated by guests as among the best in the world.

The story starts back in the 1930s when a smart and presentable young Mohan Oberoi was on holiday in the Himalayan town of Shimla—the summer refuge for the governing classes of India. Mohan’s head was turned by the grandeur of the ladies and gentlemen he saw in Shimla and without a day’s experience of hotel life to his name, he blagged his way into a job as cashier at the best hotel in town.

He must have displayed something special, because four years later the general manager of the hotel—an Englishman called Clarke—asked Mohan to go into partnership with him in the purchase of another hotel in town. Mohan had no money to speak of but used his wife’s wedding jewellery as collateral to raise his half of the down payment.

Clarke eventually wanted to return to the UK, and sold his share to Mohan who had shown himself more than capable of running the business. “Clarkes Hotel is still in the group,” says Prithvi ‘Biki’ Oberoi, son of Mohan and present chairman and CEO of the publicly listed company, “and retains the original name. It has a sentimental place in our hearts.”

Sentiment only goes so far, though. The next acquisition Mohan made was the 350 room Grand Hotel in Calcutta that had gone into receivership when it lost business after a cholera outbreak. At the time, Calcutta was an important commercial centre. “My father got the lease in 1939,” says Oberoi, “just as World War Two was starting. It was a favourite with the British officers who were desperate to get one of the 1,500 beds that were squeezed into 350 rooms and were never empty for the duration of the war.”

In 1942, Mohan pulled off what was probably the first hostile takeover in Indian history when he quietly bought up 51 per cent of the shares in Associated Hotels of India. When he announced his presence at the AGM, the British board of directors resigned en-masse but the chairman, Sir Edward Buck, agreed to stay on.

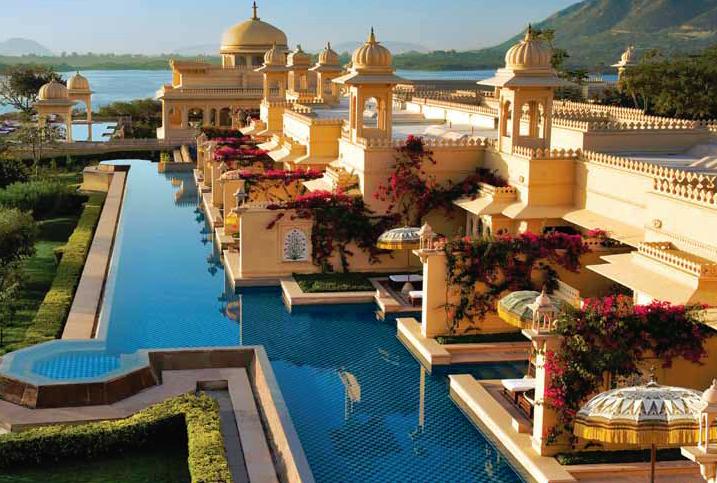

At that time, in 1942, the group had 10 hotels and it now has 30—spread from Egypt to Indonesia—trading under the brand names of either Oberoi or Trident. Oberoi mistrusts the term ‘luxury’, thinking it overused; but there is no doubt that his hotels fall into the very highest possible category. Their downtown locations, in India’s important commercial centres, cater for business people; and for those seeking a leisurely holiday, they can also be found in stunning leisure settings.

Despite being well into his 80s, Oberoi is still actively in charge of the group. He is only too aware that as he is in the business of selling service, one poorly trained or badly supervised employee could quickly wreck a reputation that has taken years to develop.

“We have converted one of our smaller hotels into a training school,” he says. “Each year, we train 30 young men and women there who have been identified as potential future general managers. It’s a two year course, after which they get hands-on experience at front of house or in the restaurant, and then the best of them are sent overseas to get international experience.”

As well as future top management, the school provides a one year course for housekeeping executives and a two year course for hotel chefs. “Some people still have the idea that the whole of India is a health risk,” says Oberoi. “We want to categorically demonstrate that this is not the case.”

The first quality all of the 12,000 strong workforce must demonstrate is fluency in English. They then need to show a willingness to leave bad habits—such as poor timekeeping—at home and provide the kind of discreet but attentive service Oberoi clientele expect.

It’s not a cheap experience to stay at one of the group’s hotels. Prices range from US$300 to $500 per night, but Oberoi argues that this is good value when compared to an equivalent hotel in the US or Europe, where prices will be two or three times higher.

The single most important business sector for Oberoi is international businessmen. “Only about 20 per cent of our clients are from India,” he says, “with most of our clients coming from the US and the UK.”

Not surprisingly, the economic climate has impacted on the group’s revenue. The accepted benchmark for occupancy is 70 per cent and in India this has slipped in the past couple of years to 65 per cent. The Mumbai terrorist attack in 2008 further compounded matters and put that particular hotel out of commission for 14 months. “The terrorist bombs and the subsequent battle with security forces,” says Oberoi, “did considerable damage and the hotel had to be practically rebuilt at a cost of $150 million.”

Oberoi himself was in Mumbai that day and would have been at the hotel had it not been for another engagement. He has nothing but praise for the staff who risked their own lives to help the unfortunate guests inadvertently caught up in the tragedy. To reward their efforts, all staff were kept on full pay for the duration of the redesign and rebuilding work. Following the refurbishment, the hotel re-opened last year and retains its reputation as an icon of quality and excellence in the very heart of India.

DOWNLOAD

OberoiGRP_APR_11_emea_BROCH_s.pdf

OberoiGRP_APR_11_emea_BROCH_s.pdf